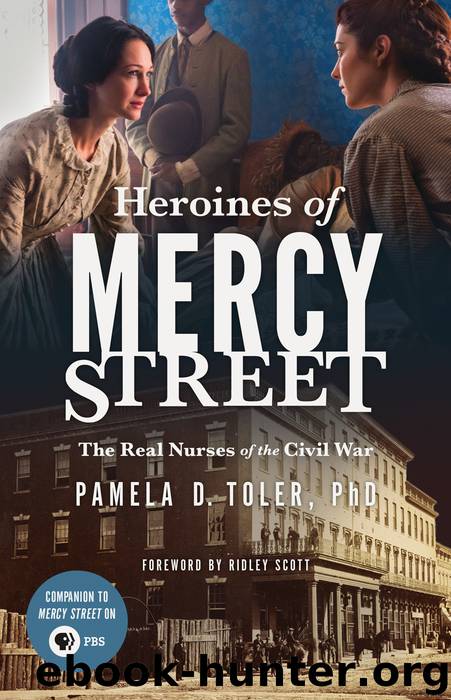

Heroines of Mercy Street by Pamela D. Toler PhD

Author:Pamela D. Toler PhD

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History / United States / Civil War Period (1850-1877), History / Women, Biography & Autobiography / Medical, Biography & Autobiography / Women

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2016-02-16T05:00:00+00:00

Tending the Whole Man

Bandaging wounds, “putting up” splints, and assisting at amputations were the most dramatic part of nurses’ work. But, in fact, most of the soldiers who ended up in the Union army hospitals were struck down by an enemy more insidious than a minnie ball from a Confederate musket. Infectious diseases, including pneumonia, cholera, malaria, dysentery, and typhoid, accounted for 64 percent of the deaths among enlisted men in the Union army. (The rate was lower among officers, who enjoyed better-quality food and less crowded living conditions, but were also twice as likely as enlisted men to be killed in action.) Providing fluids, nourishing food, clean bed linens and clothing, and physical and emotional comfort was often as important as any medical treatment.

Many of the tasks women undertook in the hospitals were domestic chores writ large: feeding patients, making beds, overseeing and sometimes doing laundry. Writing two years after the war, Jane Hoge, one of the leaders of the Chicago branch of the United States Sanitary Commission, claimed that women’s domestic skills were essential to running a hospital: “The right of women to the sphere which includes housekeeping, cooking and nursing has never been in dispute. The proper administration of these three departments makes the internal arrangements of a hospital complete.”13 Hoge wrote about the domestic aspect of nursing from the perspective of a woman who did not empty bedpans on a regular basis during the war. Women who put in their time on the hospital floor took a less elevated position on the daily chores of nursing.

Each of the domestic tasks brought its own challenges. Feeding patients, for instance, was seldom as simple as delivering trays to the bedside. Nurses coaxed along patients who had trouble digesting or were particularly weak with glasses of eggnog, milk punch, beef tea, and an occasional sip of brandy and water. The more disabled patients required physical help to eat or drink. Even carrying trays from kitchen to ward could be a challenge at some of the hospitals that had been converted from other uses, like Mansion House. Von Olnhausen groused about having to go up and down four long flights of stairs ten or fifteen times a day because she didn’t have the facilities to even warm a drop of water in her ward. “If it were not for this,” she wrote, “I would like my ward better than any other in the house; but it takes the wind.”14

Who cooked what for the patients was a political issue for hospital staffs as much as a nursing chore. Field nurses and those on the transport ships often had to cook simply because there was no one else there to do it. Georgeanna Woolsey reported she once cooked and served 926 rations of farina, tea, coffee, and “good rich soup, turkey, chicken and beef,” made from home-canned goods sent by the women of the Sanitary Commission, in a single day.15 In the general hospitals, much of the cooking was assigned to untrained

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15365)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14522)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12405)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12101)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12036)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5795)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5415)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5312)

Paper Towns by Green John(5196)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5013)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4509)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4451)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4398)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4353)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4330)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4208)